Every version of the Atlantis story, every theory, map, and debate, begins with Plato’s description of atlantis.

He didn’t claim to dream the story up. He said he recorded it, a real account passed down through Egyptian priests to the Athenian lawgiver Solon, and finally to him.

So what exactly did Plato say about Atlantis? What details survive in his own words? Let’s strip away the interpretations and look directly at his description, the foundation of everything that followed.

The Source of the Story

Plato wrote about Atlantis in two dialogues, Timaeus and Critias, around 360 BCE. These works present conversations between Socrates, Timaeus, Critias, and Hermocrates.

In them, Critias recounts a tale his ancestor Solon learned while visiting Egypt. Priests in the city of Sais told Solon that Athens once fought a great empire from across the sea — an empire that vanished after a single catastrophic event.

That empire was Atlantis.

Plato used the story to explore themes of morality, pride, and civilization, but he gave it real dates, geography, and political detail. He didn’t call it a myth. He called it history remembered by Egypt when Greece had forgotten its own beginnings.

Plato’s Description of Atlantis

Plato described Atlantis as a vast island kingdom located “beyond the Pillars of Heracles,” what we now call the Strait of Gibraltar, seen below.

Beyond those waters lay a great island “larger than Libya and Asia combined.”

Here’s what he said about it:

1. The Geography

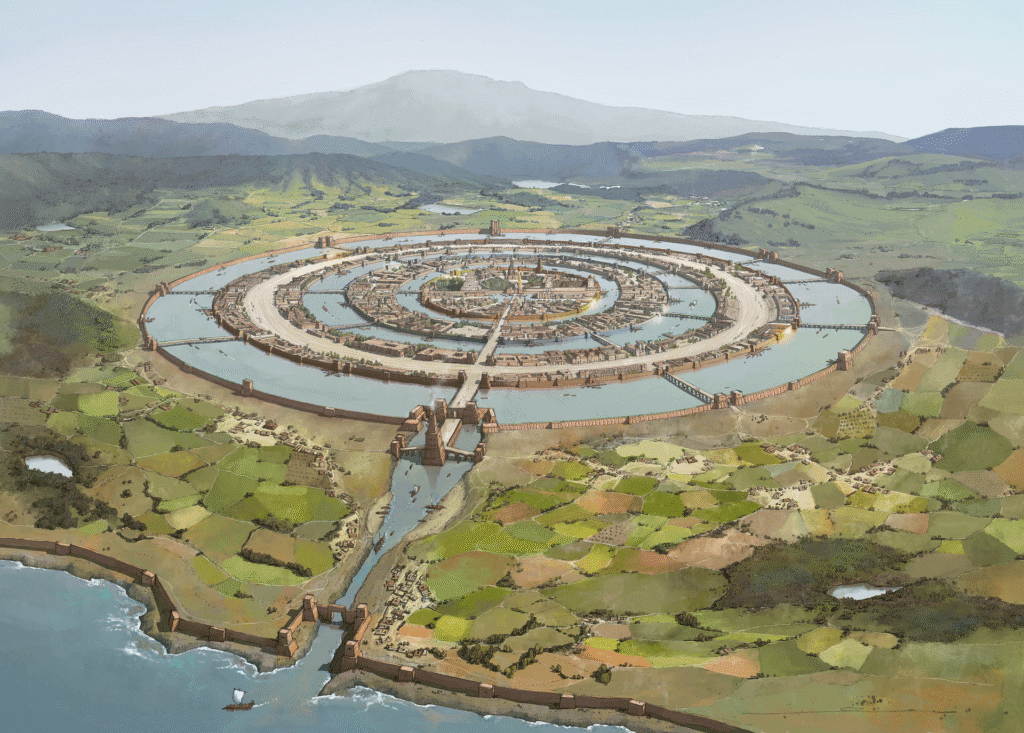

Atlantis formed a series of concentric rings, alternating bands of land and sea that surrounded a central island. Bridges and canals connected each ring.

The capital city sat at the center, crowned by a temple dedicated to Poseidon — the god who founded the island after falling in love with a mortal woman named Cleito.

The Atlanteans carved mountains, redirected rivers, and built harbors that glistened with metal. Plato described the land as rich in resources, “abundant in everything,” with forests, elephants, and precious metals.

2. The Society

Plato’s Atlantis wasn’t a primitive world. He called it an advanced maritime power, ruled by ten kings descended from Poseidon’s ten sons. Each king governed his own region, but all obeyed laws engraved on a golden pillar inside Poseidon’s temple.

Their society valued discipline, order, and virtue — at first. Over time, their wealth bred arrogance. The kings grew hungry for conquest and turned their armies against the rest of the known world.

3. The War with Athens

According to Plato, the Atlanteans launched an invasion of the Mediterranean, seeking to subjugate Egypt and Greece. Athens resisted, and won.

That victory, Plato claimed, marked the moment when moral virtue triumphed over greed and imperial power. But soon after, the gods punished Atlantis.

4. The Cataclysm

Plato wrote that earthquakes and floods struck “in a single day and night of misfortune.” The island sank beneath the sea, taking its people and their great works with it.

After that event, the sea became impassable, choked with mud and debris, the aftershock of a world lost forever.

Plato’s Timeline

Plato dated the fall of Atlantis 9,000 years before Solon’s time, roughly 11,600 years ago by modern count. That places it at the end of the last Ice Age, when sea levels rose and climate patterns shifted dramatically.

That timing still intrigues researchers today. It aligns with geological evidence of sudden global flooding — the same period known as the Younger Dryas.

Whether coincidence or clue, the match keeps the Atlantis debate alive.

What Scholars Dispute

Mainstream historians view Plato’s account as philosophical fiction, a parable warning against pride and corruption. They argue he invented Atlantis to illustrate his ideal society from The Republic — a model of order destroyed by greed.

Yet Plato never hinted that he fabricated the story. He treated it as true, naming real locations and historical figures. He claimed Solon verified the story with Egyptian priests who preserved ancient records.

That leaves a question that continues to haunt archaeology:

If Plato invented Atlantis, why did he anchor it in such detailed, consistent history?

Why Plato’s Description of Atlantis Matter today

Every Atlantis theory, from Santorini to the Sahara, depends on Plato’s description. His details create the map, the timeline, and the moral. Remove his account, and the legend collapses.

But his writing does more than describe a lost island. It captures the eternal cycle of civilization itself: creation, mastery, corruption, and fall. That pattern repeats throughout history, and maybe that’s the real reason his story endures.

Plato’s Description of Atlantis and the Search Today

Whether he wrote history or allegory, Plato launched an investigation that still drives explorers, divers, and dreamers across the planet. His vision of Atlantis continues to challenge us — not just to find a place, but to rediscover the deeper truth about humanity’s forgotten past.

Maybe that’s why the story never dies. Every clue we uncover, every ruin we unearth, brings us closer to understanding what Plato tried to preserve — a warning, a memory, and perhaps, a glimpse of who we once were.

Explore More in the Atlantis Series

- 🏛️ The Lost City of Atlantis: Uncovering the Truth Behind the World’s Greatest Mystery

- 🌍 Where Was the Lost City of Atlantis Likely Located?

- 🌀 The Eye of the Sahara: Africa’s Possible Atlantis

Final Thought on Plato’s Description of Atlantis

Plato never begged us to believe in Atlantis. He simply left us the story, a warning wrapped in mystery.

And maybe that’s the point. The power of Atlantis doesn’t come from proof. It comes from the questions it still forces us to ask.

Was he preserving memory… or planting a challenge for the ages?

Pingback: Where Was the Lost City of Atlantis Located?